Where Did Death Note Go Wrong?

by thethreepennyguignol

Earlier today, Adam Wingard, the director of Netflix’s cinematic Death Note adaptation, tweeted this:

https://twitter.com/AdamWingard/status/901333402380455937

It is, without a doubt, a response to the mauling the film is receiving from fans and critics alike. Almost all of the commentary of the film can be summed up with a wide-eyed head-shake as everyone watching tried to make sense of just how Wingard (who has a relatively solid track record, with modest successes like The Guest and You’re Next in his back catalogue) had managed to fuck up this badly. I understand why Wingard feels the urge to brush off his critics as trolls – I do. Because it’s so comically easy to rip into his Death Note adaptation for so many reasons: too reliant on knowledge of the manga to truly exist in it’s own right, but too far removed from Death Note’s more faithful versions to serve as a satisfying screen adaptation for fans of the original story, it can seem like criticism is too surface-level to be anything other than snark. Trolling is easy, and I have to admit it was tempting to just write a list of the dozens of things wrong with this movie and call it a day. But, for once, I want to approach this in as good faith as I can muster, and actually figure out why Death Note doesn’t work.

First, I think it’s worth talking about what makes Death Note such an iconic series, even today, a good decade after the initial release of the manga. I read it when I was fourteen, pinching each book from my brother’s bookcase as they were released and going through them in three-quarters of an hour each, and then having to go back over them at least three times each to put the fiendishly complicated and satisfying plot together. Much as it draws on elements of horror, fantasy, and even dystopian sci-fi, at it’s core Death Note is a detective story. It’s Sherlock and Moriarty, told from the point of view of Moriarty. When I read the series at fourteen, I had never seen anything that had so unapologetically positioned the villain as the main character, something that played endlessly with morality and justice, something so unapologetically cerebral. It’s far from perfect (the female characters are, unarguably, awfully underserved and it does lose the thread a little towards the end of the series), but it created iconic characters in Light Yagami, L, Near, and Ryuk, as well as leaning in with a po-faced sincerity to the philosophy it wanted to explore. It’s why so many people loved the manga series (and the extremely faithful anime adaptation), and why so many were excited for a new live-action version after the disastrous Japanese movie series a few years before.

So it wasn’t like Wingard didn’t have good stuff to work with here. And it wasn’t like many fans were coming to this in good faith. But the first problem that needs addressing with Wingard’s adaptation is that he seemed to fundamentally misunderstand many of the aspects of the original Death Note story that made it so compelling.

Which is not to say that every adaptation must stick slavishly to the piece of media that originated it in order for it to be good: just take something like, say, The Shining, which proves that a director bringing their own ideas to a piece of work can enhance different aspects of the story than it’s original telling. But Wingard’s changes serve to actively undermine elements of Death Note that are crucial to the story’s success.

For example, Light Turner (played by Nat Wolff, of nothing you’ve ever wanted to see) is about as far removed from the Light Yagami of the manga and anime. In those versions, Light is a high-achieving, popular, seemingly ideal high school student with a strong sense of personal justice and a streak of arrogance that grows to overwhelm him. What makes him so unsettling as a villain is that superficially he personifies many of the signifiers we associate with being a decent person. Crucially, it’s his fiendish, prodigal intelligence that lets him run his reign of terror as Kira for so long. This Light? He’s a goofy outsider, dumb enough to shout about the Death Note and what he’s doing with it in busy school corridors and revealing his secret to a cute girl whose name he only learned moments before in the hopes of getting into her pants. Flailing, useless, and dithering, the changes made to his character render the Misa stand-in, Mia, a more formidable force than light – and turn the thrilling battle of wits between him and genius detective L nothing more than a dumb-ass highschooler pouting crossly at a guy in a hoody. The movie seems to blanch at the thought of really leaning into having a villain as their leading man, giving Light a mother dead at the hands of a gangster as motivation to begin his killing spree, but still want to draw on his compelling sociopathy. They want it both ways, and all that leaves us with is a leading man who feels like he’s constantly slipping through the movie’s fingers. When the person who’s meant to be the film’s anchor is so weightless, the film threatens to float away before it even gets going.

Of course, there is no Light with L. He’s probably the most iconic character the franchise created, and maybe the only part of the film that actually sticks the landing: his intelligence, calculating nature, and personal tics are all present, supplemented with some interesting plot points regarding his relationship with his minder Watari that could have brought a new angle to the well-worn character in a film that wasn’t as rushed as this one was. Lakeith Standfield (Get Out, Atlanta) seems to have a solid grasp on the character and is about the only character who makes it unscathed from book to screen. But, no matter how good he is, when you take away to Moriarty to his Sherlock, his character is missing something fundamental and it shows, with L getting knocked unconscious for the duration of the third act because the film just couldn’t feasibly involve him without him figuring out everything that was going on and putting a stop to it. The inherent stupidness of Light undercut what could have been a really solid role for Stanfield, and I found myself wishing that this movie had just been about L instead of trying to match him up with his newly neutered nemesis.

I will admit that I was concerned about this movie from the get-go, partly because the book series is long and dense, and even a film an hour longer than this one would have trouble capturing even shades of the nuance present in the plot. But this movie, at only a hundred minutes, is forced to condense things down to an almost comical degree. Light swings between goofy outsider who just seems to want to get laid to a cold murderer willing to pick off those closest to him when the plot suits – he’s at one moment blindingly smart and the next needs to have Ryuk re-explain the rules to the book for the second time after we saw him going through them. The plot thunders by so quickly that the only thing that stands out are the mistakes, with anything interesting (like the aforementioned L/Watari relationship) not given the space to breath. When the movie quickly cobbles together Light’s master plan at the end, you can practically hear someone dusting off their hands and walking away to get a beer, glad that it’s finally over.

Speaking of things I’m glad are finally over: I truly didn’t think Wingard could come up with a movie that more deeply underserved the women characters than the original Death Note manga, but he managed it. Mia, Misa Amane’s stand in, tells Light that “nothing [she] did mattered before she met him”, and tells him that he shouldn’t bother asking to kiss her because, you know, telling teenage boys that if you think a girl wants you she for sure does is a great idea. While she has more active participation in the early stages of Kira’s rampage than in the books, that’s mainly just so she can pull the trigger on stuff that the eternally dithering Light can’t be bothered with. Apart from hornily groping at Light every time he kills someone, she’s stupid, character and motivation-free, and I’m not saying that she’s an avatar for every girl Wingard wished would build her life around him in high school, but I’m saying if someone wanted to argue that she was, I wouldn’t contest them. Oh, and she’s literally the only female character in the movie: Light’s mother is fridged prior to the beginning of the movie, while characters like detective Naomi Misora and Shinigami Rem are cut completely. And, of course, Mia dies at Light’s hand in the movie’s climactic scene, so if there are any sequels I presume we can look forward to a woman-free Death Note universe.

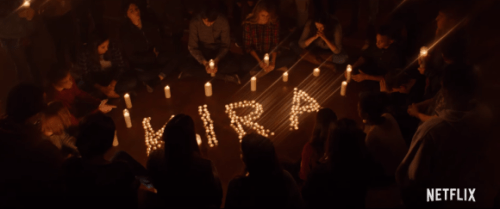

Willem Dafoe’s Ryuk deserves, I suppose, a brief going-over here since he is visually the most striking part of this movie. Arguably, Ryuk is the main character of Death Note – it’s his dropping of the Death Note into the human world out of boredom that starts the plot, and he’s the one to finish off Light at the end of the series. He’s the Greek chorus of the story, rarely interfering, and just gleefully enjoying the chaos that comes as a result of his actions.

Towards the end of the last book, when Ryuk goes to write Light’s name in the Death Note, we see this flashback to a scene that we originally saw from Light’s point of view. To Ryuk, he seems vulnerable, almost childlike, a reminder that Ryuk has always been the one with the power in their relationship despite what Light convinced himself. Ryuk has no plans, no attachment, and has no problem taking down Light when his game stops amusing him. In the film, though, Ryuk seems to imply that he passes the Death Note around human charges on purpose, and that he selected Light for reasons the film fails to satisfactorily define. He also actively interferes in the plot, his newly-invented powers an important part of the third act. Yes, he looks cool and Dafoe was always a good choice for the role, but Ryuk is another character about whom the film has apparently missed the point. From a gleeful master of chaos, he’s become an exposition machine, a Shinigami Ex Machina. I couldn’t help but think, too, that if you weren’t already acquainted with his character, you could well be lost as to what Ryuk actually is as the film does so little to introduce him or what he is or where he comes from beyond “uh, yeah, guess I’m a death god, whatever that is”.

So, that’s what’s wrong with the film when you compare it to the original Death Note story. But it’s biggest problem isn’t just that. Even if you had no idea what the original story was meant to be or what the actual characters are meant to look like, Death Note is just a badly-made film.

Okay, let me clarify that. There are actually quite a few well-directed sequences in this movie (I loved the foot chase between L and Light, with Lakeith Stanfield a graceful, terrifying silhouette against a neon-blue background), and I still think Wingard is a good man to have behind the camera as long as he doesn’t do much else. But there is so much here that is bad no matter which way you cut it: gruntingly obvious exposition, music choices so on-the-nose that sometimes I couldn’t tell whether I was meant to be in on the joke or not, death scenes that drew from Final Destination in their Machiavellian bloodiness but without the sense of fun that that iconic franchise indulged in. I could sit here and list everything wrong with this film piece-by-piece – that it seems more taken with goofy, over-the-top, and utterly charmless action sequences than with the cerebral brilliance that should define the story, that Nat Wolff seems clinically devoid of acting talent and runs like a twat, that there are a handful of mind-buggeringly annoying continuity errors that should have been picked up somewhere along the line but are infuriatingly still there.

But that would be pointless, and besides, most of you who care enough to have read this far have probably seen the movie and understand precisely what I’m talking about. Adam Wingard’s Death Note is sloppily made and falls apart under the remotest amount of scrutiny, not that you should even volunteer it that much effort. It doesn’t deserve that much. In some ways, I feel bad for Wingard, because he obviously put a lot of time, effort, and passion into adapting one of the most iconic and brilliant mangas to come out of the genre in the last ten years. But that doesn’t mean that he made a good film, just because he cared. And it doesn’t mean that everyone criticising it is a troll.

I watched Blair Witch, the Wingard-helmed sequel to The Blair Witch Project which is one of my favourite films of all time. Much like Death Note, that sequel had all the moving parts in place and Wingard approached it with passion and enthusiasm. But, in the last few minutes, Blair Witch showed us the Blair Witch, whose absence is part of the reason the original movie is so chilling. Wingard’s sequel misses that point, just like he does with so many aspects of his Death Note adaptation. As it is, I’m still waiting for the live-action adaptation of this story that does justice to just how good the story could be – and I hope that the effort and time I put into breaking down what’s wrong with this version proves to Wingard that we’re not just out here trolling him. We’re out here looking for a version of Death Note that actually gets it.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to see more like it, please consider supporting me on Patreon!