The Mystery of the Miniature Coffins of Arthur’s Seat

by thethreepennyguignol

In early July, 1836, three young boys were searching for rabbit warrens on Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh, Scotland. The craggy, rocky Arthur’s Seat, a dormant volcano that overlooks the city centre, was a popular walking spot, and had even been paved just a few years earlier in 1820, but the boys were not on the hunt for panoramic views across Edinburgh, but rabbits that they could catch to sell or use for food.

However, as the day drew on, one of the boys discovered something unusual in amongst the crags: several large, flat sheets of slate. The boys dug them loose, and, pulling them out, were met with a bizarre sight – seventeen identical coffins, each between three and four inches in size, containing small wooden figures dressed in various handmade clothes and wrappings, most decorated with small pieces of pressed metal plates to resemble real coffins.

The coffins were made up of three layers, eight on the first, eight on the second, and one on top – each layer seemed to have been deposited several years apart, going by the decay of the fabric and wood of the coffins and the figurines inside. The final coffin in the third layer appeared to have been deposited recently, perhaps in the preceding few days.

The exact series of events that transpired after the coffins were discovered by those young boys in the summer of 1836 varies, depending on whose account you believe. The Scotsman, a local newspaper, claimed that the boys had used the coffins as missiles to hurl at one another, destroying most of them, before they later shared their discovery and the remaining coffins were retrieved. The Edinburgh Evening News, more than a hundred years after the coffins were uncovered, reported that it had been a local schoolteacher who had heard of the discovery from one of the boys who had returned to the hill to remove the curios and present them to a local archaeological society that he was part of. Regardless of how the coffins actually made their descent from Arthur’s Seat, it’s generally agreed upon that the eight coffins that made it down the hill ended up under the ownership of Robert Frazer, an Edinburgh jeweller who displayed them for several years in his private collection.

Though not much information survives about how the coffins were received during this time, it seems like they gained some modest fame for Frazier and his collection – when they were auctioned upon his retirement in 1845, they boasted the description of the “celebrated Lilliputian coffins found on Arthur’s Seat” and sold for £4.80 (around £700 in today’s money) to a private collector who’s name was not recorded. From there, it wasn’t until 1901 that the eight miniature coffins reappeared, when their then-owner Christina Couper donated them to the National Museum of Scotland, also in Edinburgh, under whose ownership they have remained till this day.

So, with their origins and ownership out of the way, the question remains: what the hell were seventeen tiny, hand-made coffins with individual figures doing tucked into a hole in the side of an extinct volcano? Let’s explore what we know about the Arthur’s Seat coffins, and the theories that have been put forward to explain their provenance.

To begin with what we know about the coffins, the most comprehensive study on the eight remaining artefacts was conducted in the mid-1990s by Samuel Pyeatt Menefee and Allen D.C. Simpson. They concluded that each coffin had been cut from a single block of Scots Pine wood, with each lid made specifically for the individual coffin and secured by hand-screwed pins. Menefee and Simpson shared the opinion of then-curator Huge Cheape that the pressed metal plates bore some resemblance to similar techniques used on shoe buckles in the 18th and 19th century, and the pins in the coffins could have been found in the toolkit of a leatherworker or shoemaker, perhaps indicating the skillset or vocation of the creator. Several of the coffins had been adorned by metal plates, as might be found on real-life coffins, and two displayed remnants of pink or red paint on the lid. Several of the coffins had also been lined with a satin padding upon which the figures lay, which was identified as an offcut of fabric used to line a hat.

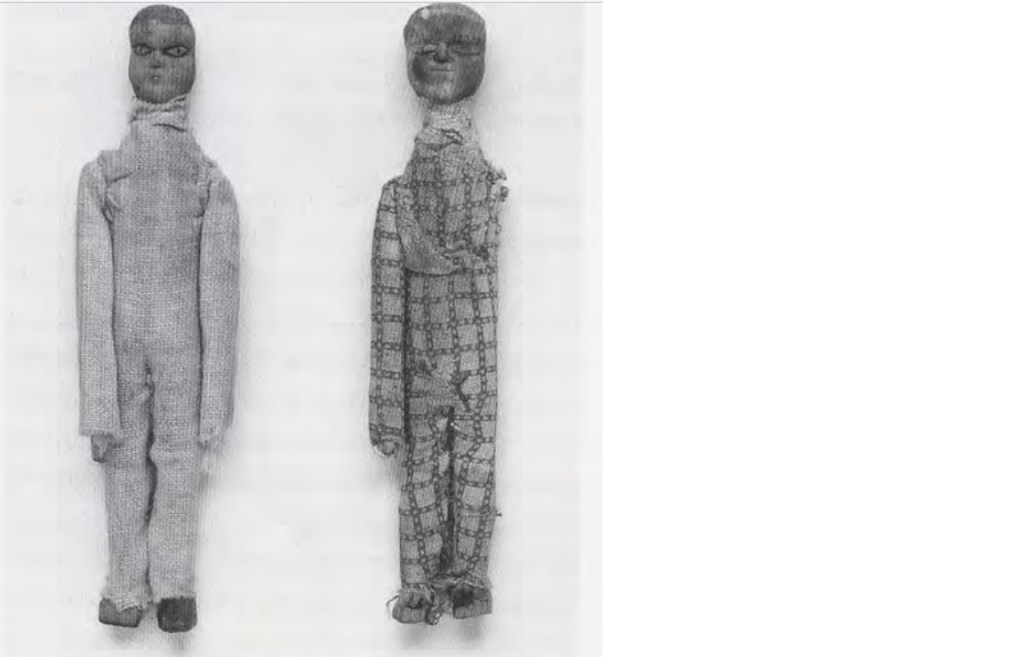

Perhaps the most interesting part of their study focuses on the figures within the eight coffins in the museum’s collection. Given the uniform nature of the figures, with “a rigidly erect bearing with straight backs, and the contours of the lower half of their bodies are carefully formed to indicate tight knee breeches and hose, below which the feet are blackened to indicate ankle boots”, Menefee and Simpson opined that they were once a collection of model soldiers modified by the creator of the coffins. The figures had been edited in various ways before being added to the coffins – the backs of their heads darkened with black pigment to represent hair, their bodies carved to change the width and size of some of the dolls, with some even missing arms, presumably to better fit into their final resting place.

The clothes found on the figures (several adhered to the dolls with glue) were believed to represent traditional grave clothes or burial shrouds, though those were not still generally in use in Scotland in the early 1800s. Each piece had stitched together from a small cut of cheap fabric, usually cotton, some of them plain and some printed with a specific pattern such as check – check out a couple of examples below.

So, with a better understanding of what the dolls and coffins actually looked like, what can we surmise about what they were made for? One of the most popular theories at the time that they were discovered was that they had been created for the purposes of an occult ritual (by “infernal hags”, as the Scotsman newspaper suggested in 1936) – perhaps the closest record we have of something like this is the corp criadhach (clay-body) recounted on Dwelly’s Gaelic Dictionary in 1911. Not far removed from the cultural depiction of a voodoo doll, in this ritual, a “clay-body”, sometimes clad in clothes, was created to represent a specific person who the spellcaster wanted to strike down with malady and death – as the clay person decayed, so too would the person it represented (unless the clay doppelgänger was discovered in time and could be preserved, thus sparing the victim). While this bears some passing resemblance to the bodies found in the coffins, crucially, it doesn’t seem as though the figures were intended to decay, a fundamental part of the corp criadhach ritual.

Other explanations suggested by contemporary sources, such as the Caledonian Mercury and the Society of Antiquities in Scotland, suggested that the dolls may have been intended to represent loved ones who had died abroad (such as sailors who died at sea), allowing their remaining family and friends to give them some kind of funeral. While the burial of effigies instead of actual people isn’t unheard of, given the three layers that the coffins were found it and the fact that they were placed in the side of a crag that was easily-accessible enough to be discovered by young boys searching for rabbits on Arthur’s Seat, this doesn’t seem a likely explanation to me either. If they had been meant to represent an actual burial for absent loved ones, would they have not been, well, actually buried?

Author Jeff Nisbet put forth the theory that the figures were related to the 1820 Radical War, a week-long uprising that saw strikes, marches, and other unrest take place across central Scotland in an attempt to improve working conditions and wages for many of Scotland’s working class after a severe economic depression had left many struggling. Several leaders in the Radical War were executed after it was quashed by the army, and, in the aftermath, unemployed weavers in the Central Belt were offered work paving a path that led up Arthur’s Seat, known as Radical Road. Nisbet suggests that the clothes the figures were found in and the location of the coffins so close to Radical Road indicated a nod to weavers who had formed such a central part of the uprising.

Which brings us to perhaps the most salacious but enduring theory about the coffins found at Arthur’s Seat: that they represent the victims of the bodysnatchers and serial killers William Burke and William Hare.

Burke and Hare operated out of Edinburgh between 1827 and 1828 – at first, they sold the body of an already-deceased victim to anatomist Robert Knox for the purposes of dissection and study, but, upon running short of corpses to sell, they began murdering people with the intent of profiting from their corpses. In total, before their apprehension and sentencing in late 1828, they committed sixteen murders, many of them lodgers in Hare’s property.

Menafee and Simpson put forward the theory in their study of the coffins that the seventeen figures originally discovered could represent the victims of Burke and Hare – the sixteen murdered, and the one who died of natural causes but whose body was denied a proper burial due to their actions. This theory posits that the creator of the coffins intended to honour the victims by putting effigies of them to rest after their actual corpses were dissected and used for study, perhaps due to guilt at their own involvement in or knowledge of the murders. Menefee and Simpson posit that the location of the coffins, in the crag at Arthur’s Seat, may have been chosen because of the desecration of local kirkyards by so-called “Resurrection Men” (body-snatchers) like Burke and Hare, or due to the proximity to Holyrood Palace, with the royal status granted to the land around it serving as a stand-in for more traditional holy ground.

It’s certainly striking that the number of coffins originally discovered matches the number of victims of Burke and Hare, especially considering the short timeframe between the two – if we’re to believe the reports that the coffins seemed to have been placed there at several intervals, there’s a chance they could have been deposited in their resting place shortly after Burke and Hare’s crimes were exposed. These crimes became a hotly-discussed scandal in Edinburgh, spawning everything from children’s rhymes to mock-executions of the anatomist who’d purchased the bodies, so it’s not hard to imagine that someone who may have felt the need to lay the victims to rest in some form had come to hear about the murders. However, Menefee and Simpson also acknowledge that the figures inside the coffins all appear to represent men, while a dozen of Burke and Hare’s victims were women, so if these coffins were intended as a mock-up of Burke and Hare’s victims, it was certainly a very broad one.

The most recent development in the case of the miniature coffins came in 2014, when the National Museum of Scotland received a strange package labelled “XVIII?” (18 in latin numerals). Inside, the sender had included a handmade replica of one of the coffins, along with a note that declared the item “a gift, for caring for our nation’s treasures, especially the VIII” (presumably referring to the eight remaining coffins that had been in the museum’s possession for the last century). The sender also included a quote from the Robert Louis Stevenson story, The Body Snatcher – which he had drawn inspiration for from, you guessed it, the exploits of Burke and Hare. The sender remains unknown, and, while it’s most likely just a gift from someone interested in the case, it’s still an interesting wrinkle to the coffin mystery.

The coffins currently reside on the fourth floor of the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, just a couple of miles from where they were first discovered. Their purpose, meaning, and creator remains unknown, but these eerie artefacts remain one of Edinburgh’s most enduring and fascinating mysteries.

If you’d like to support my blog, please consider supporting me on Patreon or dropping me a tip via my Support page.